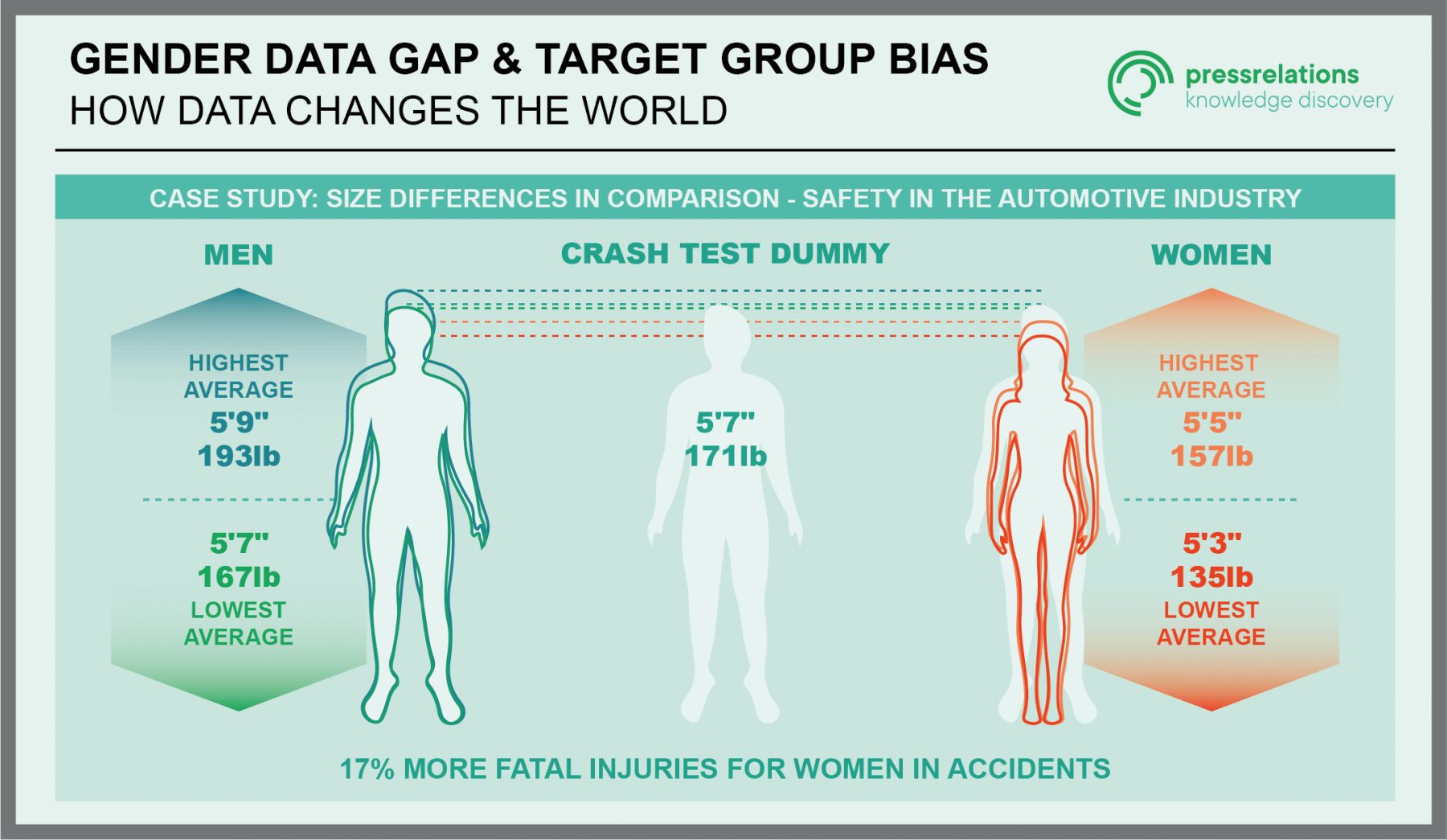

5-feet 7-inches tall and around 172 pounds – that’s what an average crash test dummy measures when it hits the wall with a car. The effects: the vehicle is demolished, splinters and fragments fly in the air, and test dummies are potentially injured. From insights gained from these tests, the auto industry can improve safety and minimize hazards to drivers. What looks like an ordinary target group analysis harbors a much more fundamental problem: the Gender Data Gap.

This Is the Gender Data Gap

The average woman – with a height of 5-feet 4-inches and a weight of about 151 pounds – corresponds to the image of the crash dummy significantly less than the average values of a man (in Germany about 5-feet 8-inches tall). The result is female drivers or passengers are at a greater risk of serious injuries. In the event of a collision, seats and protective measures such as airbags and body belts are designed for greater length and weight. In numbers, this means 17 percent more accident-related fatal injuries for women in the front seats.

The problem with the Gender Data Gap: it reflects a world in which half of humanity would not be women. After all, the data collected with crash-test dummies is not unintentional data misinterpretation and, more importantly, is not unique. The male point of view also dominates heart attack symptoms or household studies because the majority of the data we have been collecting for years, and continue to collect today, are findings of men. As a result of this bias, treatments, products, and recommendations are mistakenly based far too often on biologically male criteria, which is a real disadvantage for women.

(Source: Körpermaße der Bevölkerung – Statistisches Bundesamt)

The Gender Data Gap as a Health Risk

In medical research, the dominance of male criteria becomes a real health risk. For example, if side effects are found in female and male test groups in drug studies, the outcome of the study depends on the gender of the respective study group. If negative effects are found only in female test groups, it is usually a so-called false-negative subgroup effect, which is neglected in terms of study conduct because the number of female participants is too small to prove the effect. However, if the exact same symptoms occur in the male test group, this often means the end of that research study.

The fact that women must be represented in clinical trials at all was not enshrined in Germany until 2004 with the 12th Amendment to the German Medicines Act. Thus, initiating institutions are required to “provide evidence of the safety or efficacy of a drug, including a differential effect in women and men.”

(Source: 12. Änderungsantrag des Arzneimittelgesetzes, Seite 2039, Artikel 42, Absatz 2.)

Heart Attacks Are Detected Later in Women

However, the medical field offers many more vulnerabilities. While numerically more men suffer a heart attack, in turn, more women die from vascular, cardiac, or circulatory diseases. Why aren’t symptoms recognized earlier? The fault lies first in the system because the gender data gap is already showing its effects in research: 70 percent of the underlying animal experiments are conducted on male test subjects. While female aspects are neglected in the research of drugs against cardiovascular diseases, these should subsequently be able to be applied to any sick person in an emergency. Furthermore, there is a difference in the diagnosis of the symptoms in women: Thus, a more harmless cause is often suspected first, and treatment of acute coronary heart disease is comparatively delayed.

The list of male-biased research findings can also be found in everyday life: household studies are typically aligned with the head of the family – traditionally this role is taken by the man. Study distortions are often based on false inclusions or overlooking alternative family concepts that fundamentally contradict the study design. Female-led families are therefore less likely to find representation. Consequently, while 75 percent of men’s economic activities may be represented, only 30 percent of women’s are.

Care, medicine, security to urban planning, algorithms, and studies: the scope and risks and implications of the Gender Data Gap are as universal as data collection.

How Can the Gender Data Gap Be Closed?

Serious social deficits stem from the data gaps. The economic, social, or medical orientation of knowledge appropriation is strictly geared to the knowledge gain of the underlying research. If a part of the population disappears in invisible amounts of data, offers are not aligned for the entirety of the target group, but always aim at only a part of the whole. The resulting perception in many forms thus misses its greatest possible potential. As Melanne Verveer, Executive Director at Georgetown University’s Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, puts it, “Data not only measures progress, it inspires it.” (Source: “Closing the Gender Data Gap”)

So what to do about the gender data gap? One solution lies in its origins. Algorithms that were generated by, and consequently continue to serve, a distorted worldview must be replaced with those designed to consciously avoid these errors. As Caroline Criado-Perez, journalist and feminist, puts it in her book Invisible Women to Close the Gender Data Gap, “If we want to design a just future, we must acknowledge—and mitigate against—this fundamental bias that frames women as atypical. Women are not a confounding factor to be eliminated from research like so many rogue data points.”

(Source: „We Need To Close The Gender Data Gap By Including Women In Our Algorithms”)

But it would be wrong to persist in the pure analysis of data structures and algorithms. After all, data is a reflection of our social realities and thus also reflects stereotypes, prejudices, and male gender dominance. That’s why it’s increasingly necessary to question unjust structures and compensate for corresponding gaps. Starting with the awareness of greater participation of female researchers in the research process up to the realization of a future necessity to adapt project concepts. Equality does not necessarily mean equal treatment: the representation of biological differences is part of progress in perception and is necessary, especially in medicine, for the treatment of individuals on an equal footing. After all, it is to the benefit of all if data and the decisions that follow from it reflect actual society, and not just what prejudices and injustices that have grown over centuries stage as supposed reality.